Aperture – ISO or sensor sensitivity, shutter speed and aperture are the three basic controls the photographer has over photo exposure. ISO controls how sensitive the sensor is, shutter speed controls the length of time the shutter is open during exposure and aperture is the size of the opening on the lens.

But aperture is much more than that as it effects the depth of field in an image. Depth of field or DOF is areas that are not in focus in an image. Every modern lens is capable of sharp focus at a single plane. Changing the aperture can change how much of the image appears to be in focus.

Depending on the focal length of the lens and the aperture, images can look in focus from front to back or you can totally blow out the background into a creamy, smooth backdrop in which you can barely make out the shapes. That smooth, out of focus area is typically described as “bokeh” and different lens designs create different bokeh effects. Often professional photographers prefer a certain lens for this effect especially for portaits. Landscape photographer looking for as much overall sharpness usually are not as interested in bokeh.

In photography, bokeh (originally /ˈboʊkɛ/, /ˈboʊkeɪ/ BOH-kay — also sometimes pronounced as /ˈboʊkə/ BOH-kə,Japanese: [boke]) is the aesthetic quality of the blur produced in the out-of-focus parts of an image produced by a lens. Bokeh has been defined as “the way the lens renders out-of-focus points of light”.

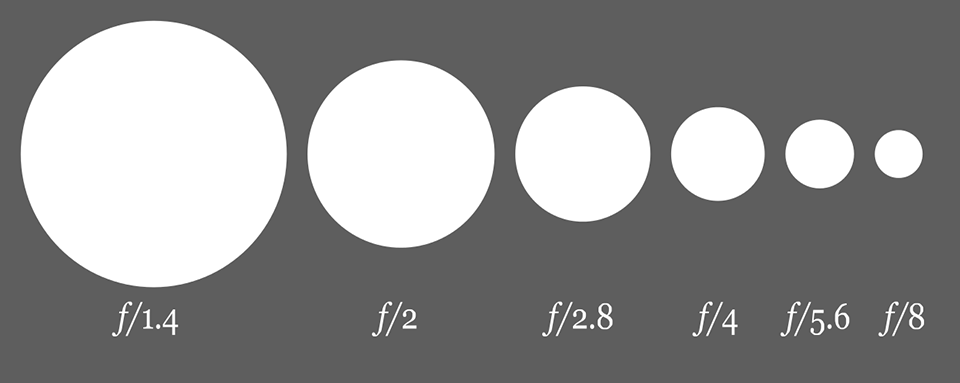

Aperture is measured in “f stops”. Smaller numbers mean larger openings. Such as f1.2 lets in more light and creates more out of focus area than say a f16.

Experiencing Aperture

Recently on the campus of the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence I was given to opportunity to experience what is happening inside a camera and the effects of aperture.

A large inflatable camera obscura was set up and groups of ten or so entered the airlock chamber, the outer door was zipped shut and then were lead into the inner dome-like chamber. After adjusting to the light, a hole in the side of the tent was uncovered and projected on white surfaces of the dome were live, upside down images of the streets around the camera obscura, demonstrating how what we see is reflected light bouncing off objects.

The four inch opening produced a bright image but a fuzzy one. Various smaller apertures were demonstrated which produced a sharper yet dimmer image. A lens was used on the larger opening to focus the light, demonstrating need of lens design. One wants as much light as possible yet needs lenses to focus that light.

Using Aperture Artistically

Too often beginner photographers seem focused on sharpness. Reading lens reviews endlessly looking for the sharpest of the sharp lens. Meanwhile professional wedding, fashion and portrait photographers invest in certain camera systems just to have certain lenses which produce amazing out of focus areas.

Sharpness in a photograph is often determined by a fast shutter-speed, a steady hand or tripod, more then the actual lens anyway. The sharpest lens ever produced hand held at a slow shutter-speed won’t produce sharp images.

Unless you are shooting sports, race cars or other moving objects, aperture choice is the most often used setting for artistry in photography. Aperture determines how much of the image you want to be in focus and how well you want to define the subject using selective focus.

In this still life photograph of baseballs, fine art photographer Edward M. Fielding uses a large aperture to throw the baseballs in the background into soft focus to pull the views eye to the main subject.

A traditional landscape photograph typically strives for a deep depth of field from front to back so smaller f-stops (higher numbers like f/11 – f/16 – f/22) are used. Ansel Adams used a view camera and lenses with very small apertures such as f/45 and up to f/64 and even started a movement called the Group f/64. DSLRs lenses typically don’t stop down this far. Also such small apertures let in such little light, long exposures and a rock solid tripod are must. Some lenses create diffraction issues at their smallest apertures and you have to watch out for dust spots as the increased depth of field betrays a dirty lens or sensor.

Landscape images don’t have to always be created with front to back sharpness. Artistic used of shallow depth of field with landscapes should also be considered such as in the following examples.

Notice how the subject of the images stands out from the background. If a shallow depth of field wasn’t uses, the clothespin or swing might have been lost in the background.

Aperture and lens choice

The effects of aperture will differ from various lens choices. Wide angle lens (24 mm and wider such as a 17mm) will have greater depth of field through out the aperture range then telephoto such as a 100 mm, 200 mm or 400 mm.

Some wide angle lenses have such a deep DOF field that you can set it at f8 and not even have to focus because just about everything will be in focus. On the downside, its nearly impossible to get a bokeh background.

Long lens inherently have a short depth of field so you have to be extra careful to focus on the eye of a bird for example, but you get a beautiful soft background.

Close focusing lenses such as macro lenses working close to subjects will also have a very shallow DOF, sometimes as small as a few millimeters.

Type of camera will also effect the DOF effect as mirror-less cameras such as micro fourth thirds cameras or small point and shoot cameras have the lens closer to the sensor than a full frame DSLR so its harder to get extreme DOF using mirror-less systems.

Aperture and Lens Cost

Canon sells a 70-200mm f/4 for $1099 and a 70-200mm f/2.8 for $800 more. Why? Because there are professional photographer who want and need that extra wide aperture and it cost more to make lenses with larger glass.

If you are a landscape photographer shooting at the smallest aperture possible, you don’t need to spend extra on the f/2.8 version. But if you are a portrait or wedding photographer wanting maximum boken, then the extra $800 is worth the price.

It’s the same with Canon’s 50mm lens line up. You can get a really inexpensive basic 50mm f/1.8 or normal lens for $125.

But for professionals wanting more shallow depth of field, Canon makes a $350 f/1.4 version.

And has found enough demand for an even more extreme shallow depth of field so they offer a $1,300 f/1.2 version.

And, you wouldn’t be buying these lenses for landscape photography on a tripod. You pay for the wide open apertures when you want to blur out the backgrounds. You aren’t paying for “more sharpness”, you are actually paying for the unfocused area of the image.